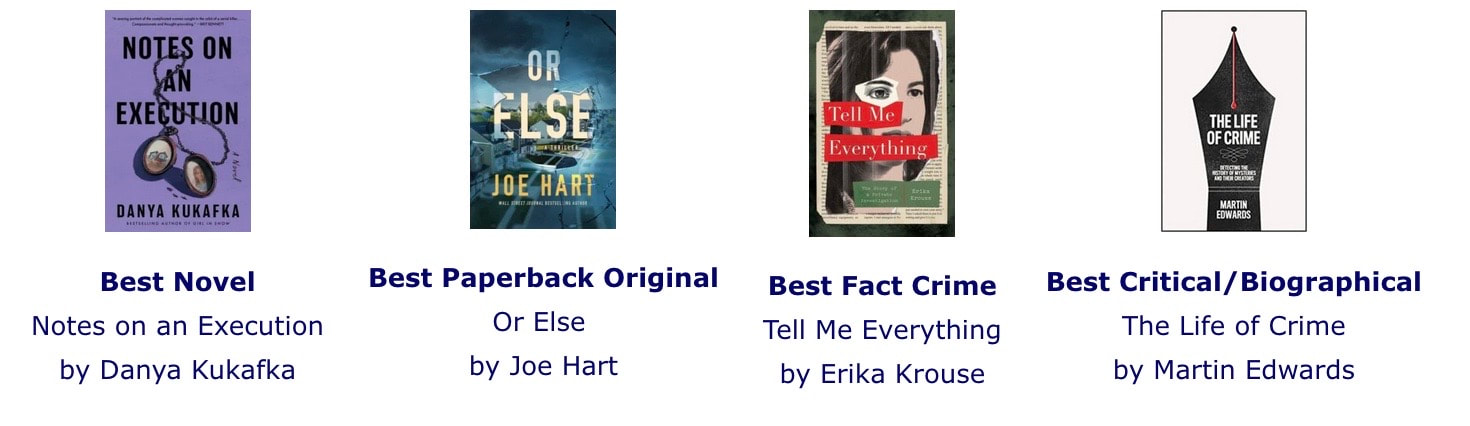

Congratulations to all the Edgar winners, and a HUGE thanks to the judges, who donated a lot of their time and expertise. The full list of winners of the 2022 EQMM Readers Award! See the printed list in the current issue.

1st Place – W. Edward BlainOne of the signs that the world is moving on from the pandemic (whether it should be considered “over” or not) is that writers are beginning to incorporate experiences from the past three years in their fiction. Experiences that were too close to explore a year or two ago are now appearing in stories submitted to us. Your choice for first place for the 2022 Readers Award is an example. W. Edward Blain’s powerful story “The Secret Sharer” (July/August 2022) grew out of teaching high school English remotely during COVID-19. The skillful incorporation of the circumstances of distant interaction between students and teachers in his plot is truly memorable, and despite the remoteness of the circumstances depicted, the story manages to be moving and surprising. Edward Blain’s first short story, “The Director’s Notes,” was published in EQMM in 1995, but by that time he already had two novels in print, the first of them, Passion Play, a nominee for the 1991 Edgar Allan Poe Award for best first novel. Since his EQMM debut, he’s contributed a half dozen other stories to our pages. For thirty-eight years he taught senior English at Woodberry Forest School in Virginia. The school and his position there obviously played a big role in the development of his short-story series featuring teacher Driscoll Henry—the series to which his winning story belongs. He has now retired to his hometown of Roanoke to write more fiction, so stay tuned! 2nd Place- Doug AllynSecond place this year goes to a Readers Award veteran. Doug Allyn is a ten-time first-place winner of the award. He’s also a multiple Edgar Allan Poe Award winner in the short-story category. Like this year’s first-place story, Doug Allyn’s winning tale “Blind Baseball” (May/June 2022) deals with a major crisis and its consequences—in this case, the Iraq War and several of its wounded and traumatized veterans. One of the Michigan author’s most innovative works, it’s essentially a quest story that incorporates smaller crime and thriller tales along the way. The author himself served in the military before becoming first a professional rock musician and then a writer. His stories have been a popular mainstay of EQMM for thirty-five years! 3rd Place -Anna ScottiA secondary-school English teacher as well as an author of young-adult fiction, short stories, and poetry published in the New Yorker and elsewhere, Anna Scotti’s first work for EQMM appeared in 2018. She has since contributed eight more stories to our pages, including several installments of her “librarian on the run” series. Last year an entry in that series took fifth place in the Readers Award voting. Your choice for third place this year was one of her nonseries stories, “Schrödinger, Cat” (March/April 2022). It’s a story that “spoke to” readers, possibly because to many of us it felt as if we’d entered into an alternate reality during the pandemic, and it is professed alternate realities that lie at the heart of this immensely clever tale! Congratulations to all of our winners!

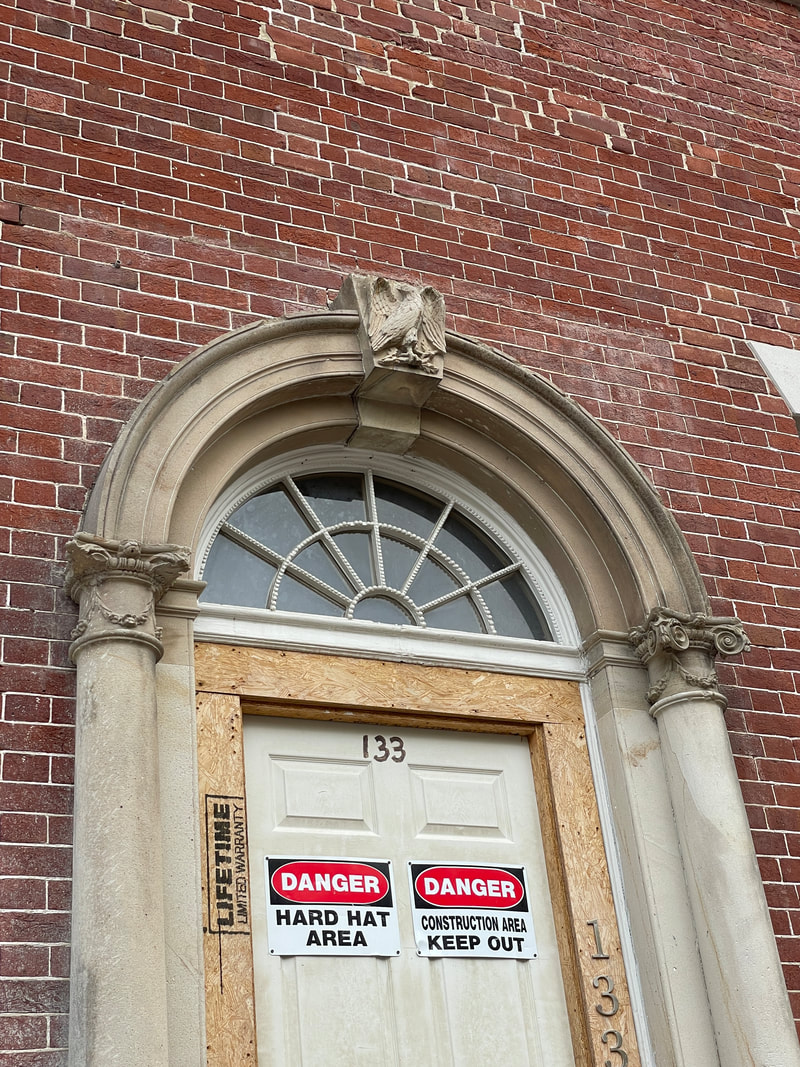

I write about mystery in a US town with constantly changing shops and restaurants, but what lies beneath is always what is most interesting - and unchanging. They are currently having to shore up a building that dates nearly to the founding of the colonial city by Scottish merchants in 1749. (The area was visited by Native Americans 13,000 years ago.)

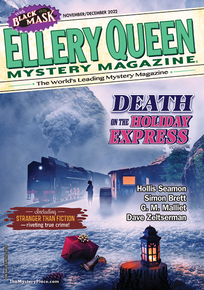

Here's what they are finding. When the restoration is finished, what used to be a bank will be a single-family home of tens of thousands of square feet. 70k? I believe was the figure.  Happy to announce my short story "Something Blue," featured on the cover of the November / December 2022 issue of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, has just been shortlisted for the EQMM Readers Award. Congratulations to winner W. Edward Blain. This story also was recently nominated for the Derringer short story award. Yesterday in Alexandria, VA. I do like the gardens but the best part is getting to troop through the beautifully decorated houses on the way to the back.

Happy Easter everyone, a day late. These Pysanky Easter eggs are 27 years old. The tradition was brought to Pennsylvania by Ukrainian immigrants who came to work the mines many decades ago.

The design is created by dipping a pin in wax and using it to paint. When the egg is dipped in dye, the design emerges. Pretty much the same principle as with the kits you buy in the pharmacy these days only much more delicate because of the pin. This photo I posted recently on FaceBook generated some interest. It is called a spite house, one of four in Alexandria, Virginia.

More at https://alexandrialivingmagazine.com/home-and-garden/queen-street-spite-house-alexandria-va-historic-alley-homes/ |

G.M. Malliet

.Agatha Award-winning author of the DCI St. Just mysteries, Max Tudor mysteries, standalone suspense novel WEYCOMBE, Augusta Hawke mysteries, and dozens of short stories. Books offered in all formats, including large print, e-Book, and audio. Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed