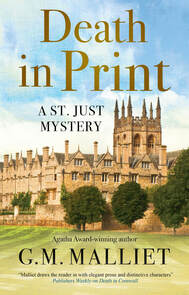

"The reader who hasn’t yet discovered Malliet's St. Just Mystery series has a real treat in store....Longtime cozy fans will be reminded of Golden Age classics starring Dorothy Sayers' Harriet Vane and Edmund Crispin's Gervase Fen.

Malliet’s writing is both smooth and elegant and her humor delicious."

Booklist starred review

Malliet’s writing is both smooth and elegant and her humor delicious."

Booklist starred review

Death in Print

Death in Print

Death in Print

A celebration in Oxford for university tutor and bestselling author Jason Verdoot, attended by DCI St. Just and his fiancée Portia, is a night to remember . . . for all the wrong reasons.

University of Oxford tutor and bestselling author Jason Verdoodt has it all: acclaim, women, money . . . and an enemy or two. When he's found dead at the bottom of the stairs during a celebratory reception at St Rumwold's College, many wonder if seething jealousy of his literary success has turned someone's mind to murder.

Detective Chief Inspector Arthur St. Just becomes inescapably drawn into an investigation that takes him down the historic streets of Oxford and into the hallowed halls of its university. Alongside his fiancée, crime fiction writer Portia De'Ath, he uncovers several motives for murdering the celebrated but insufferable Jason - whose next novel may be a threat to many in his orbit - and no shortage of suspects who are nursing a grudge from the first novel. Has someone decided to write revenge into the plot?

Available in August. Pre-order available soon.

Read the opening pages of the uncorrected proofs here:

Prologue

The Turf was crowded despite the weather. If you waited for good weather in Oxford you might never leave the house.

And she had had enough of never leaving the house. Kevin was gone and as much as she wished things were different, that was a fact.

It was time to get back out there in the world. All her girlfriends said so. But the fact was there was only one Kevin and she’d been lucky to have him. Besides, at fifty, she was getting too old for this sort of carry-on. She was more likely to make a fool of herself after more than twenty years out of the dating market than find tolerable male companionship, let alone true love.

Her friends told her there were dating apps for older people, an idea that turned her rigid with horror. She’d likely end up with one of those blokes who emptied her bank account and scarpered off back to Russia. Maisie, her sister, a religious type, thought she could meet someone if only she would join her church, showing a complete lack of understanding that any hypocrisy like that was beyond her. God had abandoned her, so she had returned the favour. The last church she had set foot in had been for the funeral service for Kevin (who had also not been religious. A man in black from the funeral home who had never met Kevin stood up before the small crowd of Kevin’s friends and pub buddies and done what he called a ‘celebration’ of his life. It might have been a celebration of any man, good or bad, with prizes just for breathing, and it carried not a trace, not a hint, of Kevin within the words, the empty words).

Still, on a Wednesday evening, it made a nice change to put on a colourful frock, the one with poppies and the belted sash that Kevin used to love. He told her she looked like a movie star in that dress, and she told him she looked more like a character actress, but ta very much. She wore a red sweater over the dress to keep out the weather.

Readying herself for these expeditions, she’d comb up her hair and even put on a little red lipstick. Not because she was trying to attract anyone but because, after a bare existence of work-eat-sleep for so long, it made her feel human. As close to human as she might ever feel again. She didn’t invite any of her friends to join her, or Maisie, who was teetotal anyway. They’d all start in with their dating nonsense, talking about how their cousin Sally met a bloke on the It’s Your Turn app, when what she really wanted was to be alone. Alone in the company of a crowd, if that made any sense at all. It made sense to her.

In the days and months after Kevin’s accident, people said wasn’t it lucky she and Kevin had never had children. Her own sister had said it – her with her twins who were ‘the light of her life’. People talked no ruddy end of rot, and as soon as she’d shut the door on them she’d say out loud – there was no one to hear, after all – all the many things she might have said but had kept inside. Only one of those many things was that she would kill to have a small version of Kevin running around the house, or a small version of herself that was part Kevin. It would be, either version, girl or boy, a child who was good with its hands, good at making things, good at getting fiddly things just right. Kevin had been a carpenter for Brice Builders, and he was so good they put him on doing the finishing work, inside and out. Mr Brice had even turned up for the ‘celebration’, which he didn’t have to do – that’s how much Kevin had meant to him. He was an artist, was Kevin, and Mr Brice had said so. Not just good at his job, but an artist. It meant everything to Kevin to reach the end of the day knowing he’d done better than his best.

All the rich folk with their fitted cabinets could thank Kevin every time they opened a perfectly balanced door that didn’t creak or come off in their hands and beheld all the expensive things they owned. Every time their roof didn’t leak, or their windows shut tight without sticking, they could thank Kevin.

But of course, they never did thank Kevin. They never knew Kevin Bottle existed. For folk like that, things they wanted to make their lives better just magically appeared. If they paid enough for the best, things would magically appear. And if some bloke fell off the scaffolding at his job building their house in a gated estate, what was it to them? They couldn’t know and they wouldn’t want to know. They would come to think of their new luxury home as a place of bad luck, haunted by a tall man with a red beard, dressed in workman’s clothes and carrying a hammer and a measuring tape. No, they wouldn’t want to know and certainly Brice Builders wasn’t going to tell them. Kevin’s accident had rated a brief notice in the Oxford newspaper, a ‘worker injured’ notice, with no follow-up when he died in hospital three days later. The world had moved on by then. The Kardashians and that lot were busy getting married again.

Yes, the world had moved on, leaving her to wish she’d never met Kevin, or that she’d never been born, or that she’d been born somewhere else than England. Anything to ease the gnawing pain that was life without Kevin.

The pub wasn’t hard to find if you were in the know, but it had become a student prank to send tourists in the other direction – to pretend they’d misunderstood and send them down Turl Street instead to the vanished pub of that name. The Turf Tavern, a completely different animal, was reached by way of St Helen’s Passage, a winding, narrow, dark alley running between a college wall to one side and a brick house on the other. Halfway along the alley was a sharp turn, but eventually the alley ran into the little ancient pub, crooked and teetering with age. It looked as if it would collapse in on itself, but according to the sign over the door it had stood since the twelfth century. Looming over it was the top of a college bell tower.

The pub was crowded but she found her favourite seat in a far corner, away from the bar, where she could be alone and observe people. She enjoyed blending into the background, keeping her eyes and ears open. Her Yorkshire granny used to say there’s nowt so queer as folk, and she was right about that. The Turf was perfect for people watching, and it had soon become a habit on her one day off a week to dress up a bit and come here for a pint on her own.

She had lived in Oxford all her life, and she had worked in an Oxford college for three years, ever since Kevin passed, for a little extra money (Kevin did like to spend) and for something to do. So she knew all the types.

The students, of course, were rowdy on a weekend night, but this was a weekday, and maybe some of them had tutorials the next day or were mindful they needed their rest. She wanted to tell them you can rest when you’re dead. You’re only eighteen, only twenty, only twenty-one, and you’re full of life and energy and you don’t have arthritis (yet) and the world’s all at your feet. You leave this place with an education the rest of the world can only envy and some of you will go on to great things. This is no time to rest up. Rest up for what – for being old and alone?

Others were tourists, and those were the fun ones to watch, easy to pick out of any crowd. Germans, Japanese, Arabs, Swedes – you name it. They were different but all the same. The Americans were the easiest to spot, however hard they tried to blend in. God bless them they tried, but everything they did gave them away, from over-tipping the barmaid on down. Their expensive travel clothes, and their accents too, of course. Their tendency to talk just that bit too loud.

Of course, in a pub they needed to shout to be heard, but not quite so much and not so often as they did shout. Their sense of belonging was what surprised her, of fitting in wherever they were, and because they had a great-great-great-uncle from Wales or Cornwall or whatever, the entire country must be their home, too. But at the same time they had this sense of wonder, like a child’s, at being surrounded by all the history – the history she herself took for granted. They were amazed at all the beautiful buildings which had been created before the United States was ever thought of. Places built by men like her Kevin, in fact.

Their shopping bags and clean new backpacks and tourist maps and tickets sprouting from their pockets – all these were clues that gave them away, but the shoes most of all. While things had changed over the years in Oxford, with people getting more casual (sloppy, she thought) all the time, the one thing that still surprised her was how easy it was to spot Americans by their shoes. All ages and sorts, the Americans wore some variation of the same brand of trainers beneath their travel pants. Maybe it was because they were on holiday and they were dressed for comfort, but she suspected they dressed like this at home, too, in what they called ‘leisurewear’.

The usual waitress came over to her to take her order, which was kind – the ritual was the customer should order a drink at the bar, however teeming it was with people, but she’d never get a drink by herself, she wasn’t the pushy type, and being here alone was enough of a personal challenge for her. It was getting easier, but still, she felt this was what Kevin would have wanted. She was easing herself back into the world, not sitting at home going slightly mad, pretending to watch some rubbish on the telly and thinking of him.

The Turf had not been her local with Kevin. That was in Cowley near where they lived. The Turf was their special occasion place when they’d been dating, and where he’d proposed, and where they’d celebrated every anniversary. Today would have been their twenty-third anniversary, and she would drink a toast – maybe two – to his memory.

The place was starting to fill up, but she’d nearly finished her pint anyway. Her second pint. She was drinking Kevin’s favourite, her own being a glass of white wine. She wondered sometimes if this was a problem, the pints. When Kevin had been around she’d never drunk much at all, really, not to speak of. But two little drinks? That was supposed to be good for the heart and the bones wasn’t it – beer especially was good for bones? Anyway, the waitress had learned her ways by now and brought the second pint without her having to ask.

She put a ten-pound note on the table as she was getting ready to leave. The £4.57 per pint was highway robbery, it was, but she’d leave the change, it wasn’t the girl’s fault. She’d just been to the cashpoint and taken out a hundred pounds; carrying round that amount of cash made her feel rich. They always said the queen never carried money, even though it had her face all over it. In the queen’s place, she’d carry a very large purse stuffed with money and she’d buy everything in cash.

But £4.57? The world had gone mad. Supply chain issues, they said. She pictured barrels of beer sitting on a big barge out in the middle of the ocean. The second beer was starting to work its magic on her arthritis. She’d worry about becoming an alcoholic another day. Maybe she was a little woozy standing up. She sat back down until it passed.

The crowd had overflowed into the beer garden at the entrance to the pub. Smoking was no longer allowed, hadn’t been for some time, and that was a blessing. She’d given up years ago at the same time as Kevin and they’d both survived it. She wondered now why either of them had bothered, but she was glad not to be tied to the habit. With the low-beamed ceilings of the tavern, it must have been like a smelly London fog in here in the past.

‘Have another, luv?’ the waitress asked, collecting her ten-pound note. ‘On the house.’

She shook her head, making its insides seem to slosh about. She was definitely feeling woozy, probably shouldn’t have had the second pint.

‘No, no. Work tomorrow,’ she said, and rose to leave. She sensed more than saw the man sitting not far from her stand up also. A tourist, well-dressed, shoes polished to a high gloss. Not American, then. Former military. Kevin had done his time and got out. He always said there were two types of people who made a career of the army: those who needed to be told what to do and those who wanted to be told. Kevin was neither type, and look how well he’d done for himself.

This time the room didn’t sway quite so much. She walked past the bar and out the door and wove her way past the throngs of students, shouting and laughing. They didn’t even see her. She was invisible. At her age she was used to being invisible among the students at the college and she didn’t hold it against them. She loved every one of them, the ones from the posh backgrounds and the ones on scholarships who were frightened so they put on airs, afraid they couldn’t keep up. Oxford had the occasional suicide at the beginning of term; that was unbelievably sad. There had only been one from her college in the years she’d been there, a boy from India who felt he was letting down his family when he couldn’t keep up with his studies, when he couldn’t fit in. She always wondered if she should have known, if she could have prevented it. She’d often seen him wandering around the quad and he looked no more lost than the rest of them. No more happy or sad than the rest of them, but it had struck her after his death that she’d never seen him in a group.

It meant so much to them to succeed, to make someone proud of them. They were all so young they made her heart ache.

She reached the lane leading from the beer garden. It would dog-leg around and take her to New College Lane and the Bridge of Sighs, her favourite spot in Oxford. It was where Kevin had first kissed her. She’d take the bus from Queen’s Lane in Oxford City Centre and she’d be home well within the hour.

She heard steps coming up behind her, heavy steps, pounding harder as whoever it was began to run. She edged to the left side of the narrow alleyway to make room. She was used to undergraduates thundering about, or zipping past her on their bicycles, never watching where they were going, nearly knocking her over a couple of times, barely stopping to apologize. The last time it had happened, a well-brought-up young man had helped her collect all the things he’d made her drop, making himself even later getting to wherever he’d been going.

But whoever this was stopped when she stopped and when she turned, looking to see who it was, what was the matter, the knife bit into the base of her throat before she could fully turn her head – it was over that quick. She never really knew who killed her, only that they were strong and they smelled of beer and cigarettes. And she knew that however much she missed Kevin, she also knew she didn’t want to die.

Not this way.

A celebration in Oxford for university tutor and bestselling author Jason Verdoot, attended by DCI St. Just and his fiancée Portia, is a night to remember . . . for all the wrong reasons.

University of Oxford tutor and bestselling author Jason Verdoodt has it all: acclaim, women, money . . . and an enemy or two. When he's found dead at the bottom of the stairs during a celebratory reception at St Rumwold's College, many wonder if seething jealousy of his literary success has turned someone's mind to murder.

Detective Chief Inspector Arthur St. Just becomes inescapably drawn into an investigation that takes him down the historic streets of Oxford and into the hallowed halls of its university. Alongside his fiancée, crime fiction writer Portia De'Ath, he uncovers several motives for murdering the celebrated but insufferable Jason - whose next novel may be a threat to many in his orbit - and no shortage of suspects who are nursing a grudge from the first novel. Has someone decided to write revenge into the plot?

Available in August. Pre-order available soon.

Read the opening pages of the uncorrected proofs here:

Prologue

The Turf was crowded despite the weather. If you waited for good weather in Oxford you might never leave the house.

And she had had enough of never leaving the house. Kevin was gone and as much as she wished things were different, that was a fact.

It was time to get back out there in the world. All her girlfriends said so. But the fact was there was only one Kevin and she’d been lucky to have him. Besides, at fifty, she was getting too old for this sort of carry-on. She was more likely to make a fool of herself after more than twenty years out of the dating market than find tolerable male companionship, let alone true love.

Her friends told her there were dating apps for older people, an idea that turned her rigid with horror. She’d likely end up with one of those blokes who emptied her bank account and scarpered off back to Russia. Maisie, her sister, a religious type, thought she could meet someone if only she would join her church, showing a complete lack of understanding that any hypocrisy like that was beyond her. God had abandoned her, so she had returned the favour. The last church she had set foot in had been for the funeral service for Kevin (who had also not been religious. A man in black from the funeral home who had never met Kevin stood up before the small crowd of Kevin’s friends and pub buddies and done what he called a ‘celebration’ of his life. It might have been a celebration of any man, good or bad, with prizes just for breathing, and it carried not a trace, not a hint, of Kevin within the words, the empty words).

Still, on a Wednesday evening, it made a nice change to put on a colourful frock, the one with poppies and the belted sash that Kevin used to love. He told her she looked like a movie star in that dress, and she told him she looked more like a character actress, but ta very much. She wore a red sweater over the dress to keep out the weather.

Readying herself for these expeditions, she’d comb up her hair and even put on a little red lipstick. Not because she was trying to attract anyone but because, after a bare existence of work-eat-sleep for so long, it made her feel human. As close to human as she might ever feel again. She didn’t invite any of her friends to join her, or Maisie, who was teetotal anyway. They’d all start in with their dating nonsense, talking about how their cousin Sally met a bloke on the It’s Your Turn app, when what she really wanted was to be alone. Alone in the company of a crowd, if that made any sense at all. It made sense to her.

In the days and months after Kevin’s accident, people said wasn’t it lucky she and Kevin had never had children. Her own sister had said it – her with her twins who were ‘the light of her life’. People talked no ruddy end of rot, and as soon as she’d shut the door on them she’d say out loud – there was no one to hear, after all – all the many things she might have said but had kept inside. Only one of those many things was that she would kill to have a small version of Kevin running around the house, or a small version of herself that was part Kevin. It would be, either version, girl or boy, a child who was good with its hands, good at making things, good at getting fiddly things just right. Kevin had been a carpenter for Brice Builders, and he was so good they put him on doing the finishing work, inside and out. Mr Brice had even turned up for the ‘celebration’, which he didn’t have to do – that’s how much Kevin had meant to him. He was an artist, was Kevin, and Mr Brice had said so. Not just good at his job, but an artist. It meant everything to Kevin to reach the end of the day knowing he’d done better than his best.

All the rich folk with their fitted cabinets could thank Kevin every time they opened a perfectly balanced door that didn’t creak or come off in their hands and beheld all the expensive things they owned. Every time their roof didn’t leak, or their windows shut tight without sticking, they could thank Kevin.

But of course, they never did thank Kevin. They never knew Kevin Bottle existed. For folk like that, things they wanted to make their lives better just magically appeared. If they paid enough for the best, things would magically appear. And if some bloke fell off the scaffolding at his job building their house in a gated estate, what was it to them? They couldn’t know and they wouldn’t want to know. They would come to think of their new luxury home as a place of bad luck, haunted by a tall man with a red beard, dressed in workman’s clothes and carrying a hammer and a measuring tape. No, they wouldn’t want to know and certainly Brice Builders wasn’t going to tell them. Kevin’s accident had rated a brief notice in the Oxford newspaper, a ‘worker injured’ notice, with no follow-up when he died in hospital three days later. The world had moved on by then. The Kardashians and that lot were busy getting married again.

Yes, the world had moved on, leaving her to wish she’d never met Kevin, or that she’d never been born, or that she’d been born somewhere else than England. Anything to ease the gnawing pain that was life without Kevin.

The pub wasn’t hard to find if you were in the know, but it had become a student prank to send tourists in the other direction – to pretend they’d misunderstood and send them down Turl Street instead to the vanished pub of that name. The Turf Tavern, a completely different animal, was reached by way of St Helen’s Passage, a winding, narrow, dark alley running between a college wall to one side and a brick house on the other. Halfway along the alley was a sharp turn, but eventually the alley ran into the little ancient pub, crooked and teetering with age. It looked as if it would collapse in on itself, but according to the sign over the door it had stood since the twelfth century. Looming over it was the top of a college bell tower.

The pub was crowded but she found her favourite seat in a far corner, away from the bar, where she could be alone and observe people. She enjoyed blending into the background, keeping her eyes and ears open. Her Yorkshire granny used to say there’s nowt so queer as folk, and she was right about that. The Turf was perfect for people watching, and it had soon become a habit on her one day off a week to dress up a bit and come here for a pint on her own.

She had lived in Oxford all her life, and she had worked in an Oxford college for three years, ever since Kevin passed, for a little extra money (Kevin did like to spend) and for something to do. So she knew all the types.

The students, of course, were rowdy on a weekend night, but this was a weekday, and maybe some of them had tutorials the next day or were mindful they needed their rest. She wanted to tell them you can rest when you’re dead. You’re only eighteen, only twenty, only twenty-one, and you’re full of life and energy and you don’t have arthritis (yet) and the world’s all at your feet. You leave this place with an education the rest of the world can only envy and some of you will go on to great things. This is no time to rest up. Rest up for what – for being old and alone?

Others were tourists, and those were the fun ones to watch, easy to pick out of any crowd. Germans, Japanese, Arabs, Swedes – you name it. They were different but all the same. The Americans were the easiest to spot, however hard they tried to blend in. God bless them they tried, but everything they did gave them away, from over-tipping the barmaid on down. Their expensive travel clothes, and their accents too, of course. Their tendency to talk just that bit too loud.

Of course, in a pub they needed to shout to be heard, but not quite so much and not so often as they did shout. Their sense of belonging was what surprised her, of fitting in wherever they were, and because they had a great-great-great-uncle from Wales or Cornwall or whatever, the entire country must be their home, too. But at the same time they had this sense of wonder, like a child’s, at being surrounded by all the history – the history she herself took for granted. They were amazed at all the beautiful buildings which had been created before the United States was ever thought of. Places built by men like her Kevin, in fact.

Their shopping bags and clean new backpacks and tourist maps and tickets sprouting from their pockets – all these were clues that gave them away, but the shoes most of all. While things had changed over the years in Oxford, with people getting more casual (sloppy, she thought) all the time, the one thing that still surprised her was how easy it was to spot Americans by their shoes. All ages and sorts, the Americans wore some variation of the same brand of trainers beneath their travel pants. Maybe it was because they were on holiday and they were dressed for comfort, but she suspected they dressed like this at home, too, in what they called ‘leisurewear’.

The usual waitress came over to her to take her order, which was kind – the ritual was the customer should order a drink at the bar, however teeming it was with people, but she’d never get a drink by herself, she wasn’t the pushy type, and being here alone was enough of a personal challenge for her. It was getting easier, but still, she felt this was what Kevin would have wanted. She was easing herself back into the world, not sitting at home going slightly mad, pretending to watch some rubbish on the telly and thinking of him.

The Turf had not been her local with Kevin. That was in Cowley near where they lived. The Turf was their special occasion place when they’d been dating, and where he’d proposed, and where they’d celebrated every anniversary. Today would have been their twenty-third anniversary, and she would drink a toast – maybe two – to his memory.

The place was starting to fill up, but she’d nearly finished her pint anyway. Her second pint. She was drinking Kevin’s favourite, her own being a glass of white wine. She wondered sometimes if this was a problem, the pints. When Kevin had been around she’d never drunk much at all, really, not to speak of. But two little drinks? That was supposed to be good for the heart and the bones wasn’t it – beer especially was good for bones? Anyway, the waitress had learned her ways by now and brought the second pint without her having to ask.

She put a ten-pound note on the table as she was getting ready to leave. The £4.57 per pint was highway robbery, it was, but she’d leave the change, it wasn’t the girl’s fault. She’d just been to the cashpoint and taken out a hundred pounds; carrying round that amount of cash made her feel rich. They always said the queen never carried money, even though it had her face all over it. In the queen’s place, she’d carry a very large purse stuffed with money and she’d buy everything in cash.

But £4.57? The world had gone mad. Supply chain issues, they said. She pictured barrels of beer sitting on a big barge out in the middle of the ocean. The second beer was starting to work its magic on her arthritis. She’d worry about becoming an alcoholic another day. Maybe she was a little woozy standing up. She sat back down until it passed.

The crowd had overflowed into the beer garden at the entrance to the pub. Smoking was no longer allowed, hadn’t been for some time, and that was a blessing. She’d given up years ago at the same time as Kevin and they’d both survived it. She wondered now why either of them had bothered, but she was glad not to be tied to the habit. With the low-beamed ceilings of the tavern, it must have been like a smelly London fog in here in the past.

‘Have another, luv?’ the waitress asked, collecting her ten-pound note. ‘On the house.’

She shook her head, making its insides seem to slosh about. She was definitely feeling woozy, probably shouldn’t have had the second pint.

‘No, no. Work tomorrow,’ she said, and rose to leave. She sensed more than saw the man sitting not far from her stand up also. A tourist, well-dressed, shoes polished to a high gloss. Not American, then. Former military. Kevin had done his time and got out. He always said there were two types of people who made a career of the army: those who needed to be told what to do and those who wanted to be told. Kevin was neither type, and look how well he’d done for himself.

This time the room didn’t sway quite so much. She walked past the bar and out the door and wove her way past the throngs of students, shouting and laughing. They didn’t even see her. She was invisible. At her age she was used to being invisible among the students at the college and she didn’t hold it against them. She loved every one of them, the ones from the posh backgrounds and the ones on scholarships who were frightened so they put on airs, afraid they couldn’t keep up. Oxford had the occasional suicide at the beginning of term; that was unbelievably sad. There had only been one from her college in the years she’d been there, a boy from India who felt he was letting down his family when he couldn’t keep up with his studies, when he couldn’t fit in. She always wondered if she should have known, if she could have prevented it. She’d often seen him wandering around the quad and he looked no more lost than the rest of them. No more happy or sad than the rest of them, but it had struck her after his death that she’d never seen him in a group.

It meant so much to them to succeed, to make someone proud of them. They were all so young they made her heart ache.

She reached the lane leading from the beer garden. It would dog-leg around and take her to New College Lane and the Bridge of Sighs, her favourite spot in Oxford. It was where Kevin had first kissed her. She’d take the bus from Queen’s Lane in Oxford City Centre and she’d be home well within the hour.

She heard steps coming up behind her, heavy steps, pounding harder as whoever it was began to run. She edged to the left side of the narrow alleyway to make room. She was used to undergraduates thundering about, or zipping past her on their bicycles, never watching where they were going, nearly knocking her over a couple of times, barely stopping to apologize. The last time it had happened, a well-brought-up young man had helped her collect all the things he’d made her drop, making himself even later getting to wherever he’d been going.

But whoever this was stopped when she stopped and when she turned, looking to see who it was, what was the matter, the knife bit into the base of her throat before she could fully turn her head – it was over that quick. She never really knew who killed her, only that they were strong and they smelled of beer and cigarettes. And she knew that however much she missed Kevin, she also knew she didn’t want to die.

Not this way.

Copyright 2023 G.M. Malliet - All Rights Reserved