|

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/43-of-the-most-iconic-short-stories-in-the-english-language

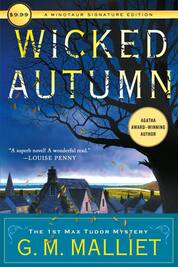

A solid list that reminds me I need to catch up on my short story reading.  Had such a fun time interviewing #LouisePenny at last week's #icelandnoir convention. She was there to promote Gamache plus her book with Hilary Clinton. Their conversation was the following day with Iceland's first lady Eliza Reid - who is also a crime writer! I was there to promote my newest Max Tudor and to see geysers and waterfalls and avoid volcanoes. Came back with a cold, but worth it. Louise and I go back a long way and it was great to catch up. Good laughs. Written interview to come.#writerslife Recommended by The Every Girl:

https://theeverygirl.com/books-to-read-for-halloween/ My local Sisters in Crime had a session yesterday led by Cathy Wiley about the uses of AI for authors.

On the one hand, for research it's a time-saving boon. On the other hand, the limits of this invention seem limitless and that's a bit frightening. I feel as if I'm being replaced, I really do -- even though the output from AI is pedestrian and not very human like, I think that is on the way. Would love to know what Goodreaders think. An excellent resource for writers just starting out or already "there," wherever "there" is.

Seriously, I recommend and not just because I'm a contributor. The collection is currently nominated for at least two major mystery awards. Making plans and arrangements to appear at the @IcelandNoir conference in Reykjavik this November. Excited! It's a place I've never been and never expected to see.

|

G.M. Malliet

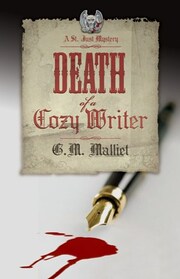

.Agatha Award-winning author of the DCI St. Just mysteries, Max Tudor mysteries, standalone suspense novel WEYCOMBE, Augusta Hawke mysteries, and dozens of short stories. Books offered in all formats, including large print, e-Book, and audio. Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed